Molentargius Regional Natural Park - Salt Pans

Orari

PARK OPENING HOURS

from 16 October to 28 February from 07:00 to 18:00

INFOPOINT OPENING HOURS

from Monday to Sunday from 08.30 to 20.30 (April-September)

infopoint@cittadelsale.com

+39 070 379191

Via la Palma, 9a, 09126 Cagliari CA

Salt Pans

The history of Molentargius is closely linked to the history of the Salt Pans. When you observe the park from the top of the Monte Urpinu hill, the close link between man, water and nature is evident, easily identifiable in the design of canals, salt pans, ponds and buildings, which has remained uninterrupted here for thousands of years.

Today, approaching the Park headquarters, you cross the Salt City of La Palma, built at the end of the 1920s and the last representative of the long history of the Cagliari salt pans which began with the Phoenicians and ended in 1985 following water pollution, an event which all the citizens of Cagliari cannot forget as it is the cause of a turning point in the relationship between the City and the wetland area.

Phoenicians, Punics and Romans were all great exporters of salt, but under the Judges the salt pans acquired international importance and were then used again by the Pisans, the Aragonese, the Spanish and the Piedmontese and lastly by the State Monopoly. During the history of the salt pans, various works have been carried out which over time have changed the shapes of the tanks, the channels, the very way of producing salt and withdrawing water. There have been numerous technological innovations. For example, around 1830 there was a technological and hydraulic reorganization of the salt pans and Archimedes’ screws moved by horses were introduced to transfer the water from one salt box to another, replaced in 1851 by a powerful steam engine.

After the production was blocked, the circulation of water was still guaranteed to allow the survival of the Molentargius pond and the entire ecosystem. Today the Park has its headquarters in one of the buildings of the City of Salt built in the 1930s: the Sali Scelti Building once intended for the purification of salt for food use.

Selected Salts Plant

The Selected Salts Plant was built in the 1930s and is today the headquarters of the Molentargius- Salt Pans Regional Natural Park. The purification operations of salt intended for food use were carried out in this plant.

The plant was equipped with a noria elevator which took the salt to the upper level where the various processing phases began. The salt was first subjected to washing in saturated water, then to a chemical treatment, centrifugation and drying with a current of air produced by a boiler. It then passed through vibrating separator screens and was finally ground and bagged. By passing through the sieves, three grades were obtained: coarse, fine and finely ground. The processing of coarse and fine salt was suspended around 1954, while fine ground salt was processed until the early 1960s. The plant fell into disuse with the evolution of salt processing techniques and was then abandoned following the abandonment of the salt production activity.

In the part behind the Sali Scelti Building there is still a dock connected to the Palma canal, used for docking the barges that transported both the salt to be purified and the salt ready for trade which was taken to the silos, known as the Nervi shed , via iron boats.

Potassium Salts Plant

The Potassium Salts Plant was built in 1939 on the edge of the vast area of the La Palma salt pans (Perdabianca) for the extraction of potassium and magnesium salts from mother liquors. The building was made up of systems similar to those of the Sali Scelti Building and was powered by the La Palma water pump with mother liquor coming from the tanks of the same name.

In those years, following the agricultural works, the market for chemical products and fertilizers increased the price of potassium salts, then imported from France and Portugal, and it was decided to build a modern plant in Cagliari capable of covering the internal and foreign market needs. Numerous small salting boxes were built where, through subsequent evaporations, the product was obtained in a thick crust, rich in impurities. The ‘potassium salt’, also known as ‘schoenite’, was nothing other than potassium chloride, present in mother liquors in the quantity of 20-25 grams per litre.

Production ceased in 1960, since then the building has been used as a warehouse for several years and is now abandoned.

City of Salt

The ‘Salt Village or Salt City’ was built around the 1920s and 1930s and includes a set of buildings including the homes of the managers and employees of the salt pans, the rooms where the salt was processed and community spaces. The ”City of Salt” at that time represented a new model of production complex, made up not only of works linked to the industrial cycle, but of the integration of the workplace and residences and took up the model of the mining and industrial villages built in other areas of Sardinia in those years.

Among the buildings, one of the most majestic, recently renovated, is the Palazzo della Direzione, built starting in the 1930s and located at the entrance to the Villaggio del Sale. Inside there are still the doors of the time and the handcrafted furniture built by the carpenters of the salt pans. Next to the Management Building is the Church of the Holy Name of Mary, built for the saltworks employees and designed by the manager of the technical services of the saltworks, Eng. Vincenzo Marchi. After years of decay and abandonment it was restored and since September 1991 it has been used for carrying out special ceremonies.

At the confluence between the main navigable canal and the Terramaini canal we find the former headquarters of the Dopolavoro. The building, inaugurated on 20 October 1932, was once part of the Opera Nazionale Dopolavoro and is made up of a performance hall and associated services. It has currently been granted to a theater company that takes care of the management and maintenance of the ”Teatro delle Saline’.

Then there are the spaces of the workshops, the carpentry shops, the warehouses, the canteen, the changing rooms, the offices and the chemical laboratory which present the characteristics of single-storey industrial factories divided into two copies of parallel buildings.

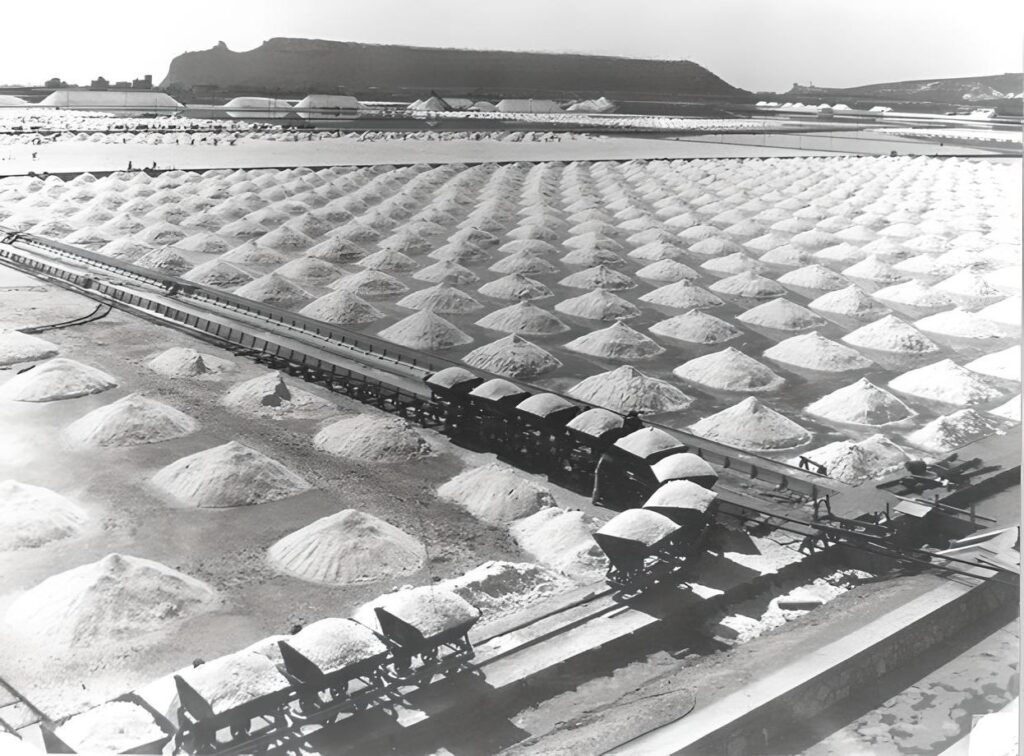

Also part of the village are the caretaker’s house and the locomotive shed where maintenance was carried out on the hydraulic locomotives that pulled the small wagons used to transport salt from the collection areas to the processing plants along the network of tracks.

The ruins of the salt pans including the Rollone pump are preserved in the village.

Bromine Salts Plant

The Bromine Salts Plant consists of some low bodies and a red brick chimney. The surrounding area was once called ‘the little salt pan’ of La Palma’, where work was done with mother waters. The facility housed bromine processing, treatment, storage and glass packaging facilities and used the concrete cylinder for bromine refining processes.

Production began in 1940 with 800-900 kilograms per day. Bromine was used for the rectification of petrol produced in Romania, energy resources used by our armed forces. Production, expensive and complex, was interrupted in 1943 and resumed for just three years in 1957.

Rollone water pump

The Rollone water pump” indicates the building that contains three electric pumps, one of which is still functioning. Their function was to take water from the tanks to convey it to the pond or the sea and to supply the salting tanks with sea water via the floodgates connecting to the canals. The water pump worked using an Archimedes wheel driven first by animals, then by steam engines and then in more recent times by internal combustion and electric engines.

The origin of the name seems linked to the roller used in the past to regularize the surface of the basins, but also to the old steam-powered water pumps which had the appearance of large wheels. On Rulloni was the tympanum, a large Archimedes wheel, equipped with buckets that caught the water and carried it from the bottom up, discharging it into a canal.

Next to the water pump are the building that housed the salt workers and an electrical power station with distribution cabin, on the other bank of the canal you can still see the ruins of the shelter for convicts.

Work in the Salt Pans

Until the early 19th century, work in the salt pans, which was particularly hard both due to physical fatigue and environmental conditions, was carried out through the worker recruitment system known as ”comandate” which required free citizens to abandon their jobs. and the fields during the harvest period to go to work in the salt pans almost for free.

Charles Albert abolished this system and employed ‘convicts’ who left dramatic letters as evidence of the hard work they were forced to do. In 1898 the State decided to assume direct management of the salt pans and abolished the use of convicts (‘salt damned’) in 1929.

Once the plants were renovated, the manual work was divided between the specialized and qualified employees and the general laborers hired during the harvest period. In the 1920s, the first salt workers’ cooperatives were formed in Cagliari, Quartu, Quartucciu and Monserrato, which joined forces to avoid competition in the assignment of work lots. Children were also used, mostly children of salt workers, who brought water to drink, therefore called ‘acquaderisi’ or removed the mud deposited together with the salt in the heaps, ‘politterisi’.

After the Second World War, manual work was replaced by rail transport and the collection was improved with the use of mechanical shovels. During the history of the salt pans, various works were carried out which over time modified the shapes of the tanks, channels and the very way of producing salt.

The work in the salt pan was divided into several phases, the methods of execution of which took on significantly different characteristics over the years:

the collection and accumulation of salt in the salt basins which took place with the process of the attelatura and the regatte and following the mechanization of the salt pans, in the 1960s, through the harvesting machine and the trains;

the salt treatment which consisted of washing, purification, adulteration and quality control operations;

transport to the Nervi warehouse which took place until the 1960s with iron boats, from the 1960s via trains and from 1975, when the silo fell into disuse, directly to the ships via trucks;

boarding ships.

Water circulation

When the salt production activity was in operation, the Molentargius pond and part of the Quartu pond were used as first and second evaporation tanks, the water then continued in the third evaporation tanks and subsequently in the salting tanks of Rollone, of the Mezzo and Palamontis, where the collection of sodium chloride or sea salt took place. The hydraulic operation of the Cagliari salt pan was mainly based on the natural movement of water by falling from one basin to the next and there were two lifting stations (Rollone water pump and Palamontis water pump) for the internal movement and discharge of the water, as well as to the lifting station for water intake (Poetto pump).

Until the 1960s, sea water was collected at the entrance to the Palafitta (Su Siccu) by tidal motion and from here the water reached the Molentargius and the Rollone water pump. The water was then sent to the salting basins where the precipitation of sodium chloride occurred. The remaining water (mother water) was removed and sent to Palamontis, in the collection basins for the production of magnesium salts and from here, via the Palamontis water pump, the water was sent to the Salina della Palma for the processing of the salts of Potassium and subsequently of Bromine salts.

Since the 1950s the mother liquors have no longer been used and the Salina di La Palma was transformed first into salting and then evaporating tanks. From 1960 to the 1980s, sea water was pumped from the pumper located near the old Marine Hospital which fed the La Palma salt pan and the Molentargius via the canal called ”Sea or loading canal” and the ‘ ‘Mortu Canal’. In the Molentargius pond the waters concentrated and exited via the ”Bassofondo Canal” directed towards the Rollone water pump. From here it was sent to the evaporation tanks and then in the spring to the salting tanks, the water evaporated and deposited the sodium chloride. Once a thickness of 20-25 cm was reached, towards the end of August the salt harvesting began.

After the interruption of production, the circulation of water was maintained exclusively in order to protect the delicate ecosystem and avoid its drying up. As part of the Safeguard Program works, the Poetto water pump was replaced by a sea pump, located approximately 450 m from the coast, which collects the water which then reaches a lifting station located near the road by gravity. Poetto coast and from here sent into the canal that feeds the entire complex.

Salt Pans, an environmentally friendly industry

According to the study ‘Salina, an environmentally friendly industry’ by Joseph S. Davis, of the Department of Botany of the University of Florida, salt production would have positive repercussions on the environment. The research work ‘La Salina, an environmentally friendly industry’ by Joseph S. Davis can be freely consulted in the web.

Natural influences in salt production

The dynamics linked to productivity in the salt marshes and the landscape are influenced by numerous climatic factors, such as sea conditions, the characteristics of the coast and geographical position, the climate and atmospheric phenomena.

Sea conditions directly affect the performance of a saltworks. In particular, the degree of salinity and the amplitude of the tide are the most relevant elements within this relationship. The amplitude of the tide allows the penetration of sea water into the salt pan and is a factor that influences the structure of the salt pan and to some extent the final cost of the product, having, in the absence of a sufficient tide, to artificially raise the water . From this point of view, the comparison between oceanic salt pans and Mediterranean salt pans is interesting. In the former, the salt pans are made up of three distinct parts: 1) a vast depression; 2) evaporating basins, 3) salting boxes. During the great tides the sea water penetrates through channels into the vast depression, where the water necessary to feed the salt pan collects, thus performing the function of a collection tank. In the Mediterranean salt pans, however, there are no large depressions and consist only of salting boxes and evaporating basins where the water, to circulate in the different series of tanks, must be raised one or more times with different methods.

The nature of the soil is also of great importance, which must not be rocky because it is too hard, nor too sandy because it is unstable, but must be plastic and waterproof, so as to avoid infiltrations and losses of already concentrated water in the salt pans. In the past, to overcome the problem of soil permeability, clay deposits were applied inside the salt pans. A temporary and expensive solution that required constant maintenance, as the tanks were subjected to considerable degradation.

Another particularly influential factor is the climate. Temperatures, precipitation, the strength and frequency of winds can favor or not favor the productivity of salt marshes, precisely because evaporation is related to these elements. A favorable climate picture presents itself with high pressure, high temperature, little cloudiness and frequent winds. The presence of a dry season has a positive influence on a good level of productivity, as the rain dilutes the water, preventing or delaying its concentration, while on the other hand, ventilation is of great importance, essential for intense evaporation. The rate of evaporation is proportional to the difference between the maximum vapor pressure of water at room temperature and its pressure in the atmosphere. In other words, by driving away the vapor present in the air, the wind decreases this pressure and activates evaporation. In this regard, land winds have a more effective effect than those coming from the sea, which are much wetter than the former. In salt pans where the predominant winds are the Sirocco or the Levante, for example, lower productivity levels could be obtained compared to salt pans where the Mistral is the dominant wind, drier than the previous ones.

Studying the strength and frequency of winds is therefore of great importance for a profitable salt industry. The different productivity of salt marshes therefore depends almost exclusively on the different climatic conditions of the areas in which they arise.

The differences in climatic conditions not only affect the performance of the plants but also the salt extraction technique, which brings notable diversity to the landscape itself and, consecutively, to the same surface of the salt pans.